Home Run Baker

| Home Run Baker | |

|---|---|

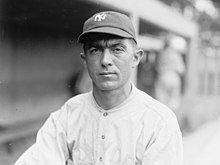

Baker in 1921 | |

| Third baseman | |

| Born: March 13, 1886 Trappe, Maryland, U.S. | |

| Died: June 28, 1963 (aged 77) Trappe, Maryland, U.S. | |

Batted: Left Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| September 21, 1908, for the Philadelphia Athletics | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 29, 1922, for the New York Yankees | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .307 |

| Home runs | 96 |

| Runs batted in | 991 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Managerial record at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1955 |

| Election method | Veterans Committee |

John Franklin "Home Run" Baker (March 13, 1886 – June 28, 1963) was an American professional baseball player. A third baseman, Baker played in Major League Baseball from 1908 to 1922 for the Philadelphia Athletics and New York Yankees. Although he never hit more than 12 home runs in a season and hit only 96 in his major league career, Baker has been called the "original home run king of the majors".[1]

Baker was a member of the Athletics' $100,000 infield. He helped the Athletics win the 1910, 1911 and 1913 World Series. After a contract dispute, the Athletics sold Baker to the Yankees, where he and Wally Pipp helped the Yankees' offense. Baker appeared with the Yankees in the 1921 and 1922 World Series, though the Yankees lost both series, before retiring.

Baker led the American League in home runs from 1911 to 1914. He had a batting average over .300 in six seasons, had three seasons with more than 100 runs batted in, and had two seasons with over 100 runs scored. Baker's legacy has grown over the years, and he is regarded by many as one of the best power hitters of the deadball era.[2] During his 13 years as a major league player, Baker never played a single inning at any position other than third base. Baker was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1955.

Early life

[edit]John Franklin "Home Run" Baker was born on March 13, 1886, to Franklin Adams Baker and Mary Catherine (née Fitzhugh) on their farm in Trappe, Maryland.[3][4] The Bakers, who were of English descent, had been farmers in Trappe for six generations. His mother, of Scottish descent, was reported to be a distant relative of Robert E. Lee.[2][4]

Baker enjoyed working on his father's farm, but he aspired to become a professional baseball player from the age of ten. In Trappe, most of the residents attended the local baseball team's games on Saturdays.[5] Frank's older brother, Norman, was well known in the town for his playing ability. Norman once tried out for the Philadelphia Athletics, but he did not like that city and stopped pursuing a baseball career.[4]

Baker attended Trappe High School and played for their baseball team as a pitcher and outfielder.[6] He also worked as a clerk at a butcher shop and grocery store owned by relatives.

Semiprofessional career

[edit]Baker signed with a local semi-professional baseball team based in Ridgely, Maryland, in 1905, at the age of 19. The team, which was managed by Buck Herzog, paid him $5 per week ($170 in current dollar terms) and covered his boarding costs. Herzog found that Baker could not pitch well, but that he could hit. Baker was unable to play the outfield well, but he was able to move into the infield as a third baseman for Ridgely.[2][7]

In 1906, Baker played for Sparrows Point Club in Baltimore, earning $15 per week ($509 in current dollar terms). He received an offer to play for a team in the Class C Texas League in 1907, which he turned down. He instead signed with an independent team based in Cambridge, Maryland.[2]

Professional career

[edit]Minor leagues

[edit]A scout for the New York Giants of the National League noticed Baker while he was playing for Sparrows Point. They arranged for Baker to receive a tryout with the Baltimore Orioles of the Class A Eastern League late in the 1907 season.[8] Playing in five games, Baker recorded two hits, both singles, in 15 at-bats. Orioles' manager Jack Dunn decided that Baker "could not hit", and Baker was released.[2]

In 1908, Baker began the season with the Reading Pretzels of the Class B Tri-State League. He had a .299 batting average in 119 games played, adding six home runs, 65 runs scored, and 23 stolen bases.[2][9]

Philadelphia Athletics (1908–1914)

[edit]Connie Mack, the manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, purchased Baker's contract in September 1908. In nine games, Baker batted .290 in 31 at-bats to close the 1908 season.[2][9] Mack named Baker his starting third baseman for the 1909 season. That year, Mack established his "$100,000 infield", with Baker joined by first baseman Stuffy McInnis, second baseman Eddie Collins, and shortstop Jack Barry.[10] He hit .305 with a .447 slugging percentage and four home runs for Philadelphia in 1909, including the first home run to go over the fence in right field of Shibe Park. His slugging percentage was fourth best in the American League, while his 85 runs batted in (RBIs) were third-best, and his 19 triples led the league. The Athletics improved by 27 wins over their 1908 record in 1909, but finished in second place behind the Detroit Tigers.[2]

In a late season series against the Tigers in 1909, Ty Cobb spiked Baker while sliding into third base, lacerating Baker's arm. Baker referred to the spiking as "deliberate" on the part of Cobb,[11] while Mack called Cobb the dirtiest player he had seen,[2] and asked American League president Ban Johnson to investigate. A photograph taken for The Detroit News vindicated Cobb, by showing that Baker had to reach across the base to reach Cobb.[11] Though Baker remained in the game after wrapping his arm, he acquired a reputation for being weak and easily intimidated.[2] Joe S. Jackson, a sportswriter for the Detroit Free Press, referred to Baker as a "soft-fleshed darling".[11]

In the 1910 season, Baker led the American League with 11 home runs in 1911, and batted .344.[2] Baker helped the Athletics win the 1910 World Series over the Chicago Cubs, four games to one, as he batted .409 in the five-game series.[12]

In the 1911 World Series, the Athletics faced off against the Giants. Based on Baker's past run-in with Cobb, Giants players believed they could intimidate him. Fred Snodgrass spiked Baker while sliding into third base in Game One, knocking the ball loose and requiring Baker to bandage his arm. In Game Two, Baker hit a go-ahead home run off Rube Marquard for an Athletics win. He hit a ninth-inning game-tying home run off Christy Mathewson in Game Three. Later in the game Snodgrass again attempted to spike Baker, but he was able to hold onto the ball and the Athletics won again.[2] A six-day delay between games as a result of rain, which turned Shibe Park into a "virtual quagmire", allowed Baker's feats to be magnified by the Philadelphia press, during which time he began to be referred to by the nickname "Home Run".[13] The Athletics defeated the Giants in six games, as Baker led the Athletics with a .375 batting average, nine hits and five RBIs in the series.[2][9]

Baker again led the American League in home runs in 1912, and led the league with 130 RBIs as well.[14] But his Athletics finished in third place, and the Boston Red Sox defeated the Giants in an exciting eight-game World Series.[15] In 1913, he again led the league with 12 home runs and 117 RBIs, but this time the Athletics defeated the Giants in the World Series, as Baker batted .450 with a home run and seven RBIs in the five games. He led the league in home runs for a fourth consecutive season in 1914, with nine,[2] despite suffering from pleurisy during the season.[16] He also batted .319 and added 89 RBIs, 10 triples and 19 stolen bases.[17] Late in the season, Mack sent Baker, Collins and pitcher Chief Bender to scout the Boston Braves, their opponent in the 1914 World Series.[18] Despite predictions that Philadelphia would win the series handily,[17] the Braves defeated the Athletics four games to none, as Baker batted only .250.[19]

After the 1914 World Series, Mack began to sell off some of his best players[2] not including Collins, to whom he had given a multiyear contract during the regular season to prevent him from jumping to the upstart Federal League.[16] Baker, who had just completed the first year of a three-year contract, attempted to renegotiate his terms, but Mack refused.[20] Baker sat out the entire 1915 season as a result of this contract dispute.[21] He remained in baseball, playing for a team representing Upland, Pennsylvania, in the semi-professional Delaware County League.[2][22]

New York Yankees (1916–1919, 1921–1922)

[edit]

Pressured by American League president Ban Johnson, Mack sold Baker's contract in 1916 to the New York Yankees for $35,000 ($980,000 in current dollar terms).[2][9] Even though Baker reported to the Yankees with an injured finger, and he injured his knee during a game in May, he and Wally Pipp combined to form the center of the Yankees' batting order. Pipp led the American League in home runs with 12 in 1916; Baker finished second with 10, despite missing almost a third of the Yankees' games.[23][24] Pipp hit nine home runs in 1917, again leading the league.[23] Baker led the league with 141 games played in the 1919 season. The Yankees hit a league-leading 47 home runs that year, of which Baker hit ten.[2] Sports cartoonist Robert Ripley, working for the New York Globe coined the term "Murderer's Row" to refer to the lineup of Baker, Pipp, Roger Peckinpaugh, and Ping Bodie.[25]

Baker sat out of baseball during the 1920 season, as his wife died of scarlet fever. His two daughters were also affected, but they were able to recover.[2] Late in the 1920 season, Baker again played for Upland, and stated his desire to return to New York. He rejoined the Yankees in 1921, as the Yankees reached the World Series for the first time in franchise history. Missing the last six weeks of the 1921 season, Yankees' manager Miller Huggins started Mike McNally in his place. In the 1921 World Series, a best-of-nine series, Huggins opted to start McNally over Baker, though he wanted to be sure to take advantage of Baker's World Series experience.[26] The Giants defeated the Yankees five games to three; Baker played in only four of the eight games, though McNally struggled to a .200 batting average.[27]

In the 1922 season, Baker played in 66 games. Overshadowed by Babe Ruth as a home run hitter, Baker complained about the "rabbit ball", saying that the ball being used traveled much further than the ball used for the majority of his career.[2] The Yankees again faced the Giants in the World Series, losing four games to none. Baker received only one at bat in the 1922 World Series.[28] He finished his career as a Yankee with a .288 batting average, 48 home runs and 379 RBIs in 676 games.[29]

Managerial career

[edit]Following his retirement as a player, Baker managed the Easton Farmers of the Eastern Shore League during the 1924 and 1925 seasons. He was credited with discovering Jimmie Foxx and recommending him to Mack. After Baker sold Foxx to the Athletics, the Farmers fired Baker, because they believed Mack did not pay a high enough price for Foxx.[2]

Personal life

[edit]Baker was a modest man who never drank, smoked, or swore.[30][31] He returned to his Maryland farm every offseason, where he enjoyed duck hunting.[2] While playing in Cambridge, Baker met Ottilie Tschantre, the daughter of a Swiss jeweler. They were married on November 12, 1909.[8]

Baker and his wife had twin babies in late January 1914. The babies were reported as doing well a couple of days later, but they died before they were two weeks old. The twins were initially reported as being a boy and a girl by The New York Times, but they were reported as twin girls by the same publication a few days later.[32][33] After the 1919 season, his wife contracted scarlet fever and died.[2] He remarried, to Margaret Mitchell, after leaving the Yankees.[2]

In addition to working on his farm, Baker served Trappe as a member of the Trappe Town Board, a tax collector, and a volunteer firefighter. He was also a director of the State Bank of Trappe.[2] In 1924 Baker intervened to stop the lynching of a black man in Easton, Maryland who had assaulted Baker's sister-in-law.[34][35]

On June 28, 1963, Baker died about two weeks after having a stroke.[36] He was survived by his wife and two children from each of his two marriages.[37] He was interred in Spring Hill Cemetery in Easton, Maryland.[2]

Legacy

[edit]

Though nicknamed "Home Run", Baker hit only 96 home runs in his career, and never more than 12 in a season as he played during the dead ball era.[9] Walter Johnson referred to Baker as "the most dangerous batter I ever faced."[9]

Baseball historian Bill James rated the 1914 edition of the $100,000 infield as the greatest infield of all time, and also ranked the 1912 and 1913 editions in the top five of all time.[38]

In 1955, the Veterans Committee elected Baker into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.[39] He was also inducted into the baseball hall of fame for Reading, Pennsylvania.[9] Lawrence Ritter and Donald Honig included him in their 1981 book The 100 Greatest Baseball Players of All Time.[citation needed] In his 2001 book The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, Bill James ranked Baker the 70th greatest player of all time and the 5th greatest third baseman.[38]

Home Run Baker Park in his hometown of Trappe is named for him.[6]

See also

[edit]- List of Major League Baseball career triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball players to hit for the cycle

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball home run records

- List of Major League Baseball annual home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual triples leaders

- Major League Baseball titles leaders

References

[edit]- ^ "Home Run Baker Accepts Bid to Banquet Here: Oldtimers To Honor Swat King of Past". Reading Eagle. January 20, 1950. p. 20. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Jones, David. "Home Run Baker". SABR Baseball Biography Project. Society of American Baseball Research. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ "Baker, Frank". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved September 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c Sparks, p. 5.

- ^ Sparks, p. 3.

- ^ a b "Eastern Shore Legends: Home Run Baker".

- ^ Sparks, pp. 7-8.

- ^ a b Sparks, p. 11

- ^ a b c d e f g Reading Eagle via Google News Archive Search

- ^ The Pittsburgh Press via Google News Archive Search

- ^ a b c Sparks, p. 31

- ^ "1910 World Series – Philadelphia Athletics over Chicago Cubs (4-1)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ Sparks, p. 75

- ^ "1912 American League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ "1912 Philadelphia Athletics Batting, Pitching, & Fielding Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Sparks, p. 134

- ^ a b Sparks, p. 137

- ^ Sparks, p. 136

- ^ "1914 World Series – Boston Braves over Philadelphia Athletics (4-0)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ The Pittsburgh Press via Google News Archive Search

- ^ The Day via Google News Archive Search

- ^ Lanctot, Neil (1994). Fair Dealing and Clean Playing: the Hilldale Club and the development of black professional baseball, 1910–1932. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 11. ISBN 0-89950-988-6.

"Semiprofessional" may be a euphemism. Upland employed other major leaguers between 1915 and 1919 (including Baker's longtime teammate Chief Bender), but by 1919 the Delaware County League was declared an outlaw league by organized baseball. - ^ a b Anderson, Bruce (June 29, 1987). "A Pipp of a Legend: The Man Who Was Benched in Favor of Iron-Horse Lou". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ The Day via Google News Archive Search

- ^ Istorico, Ray (2008). Greatness in Waiting: An Illustrated History of the Early New York Yankees, 1903–1919. McFarland. p. 189. ISBN 9780786432110.

- ^ Sparks, pp. 227-228

- ^ "1921 World Series – New York Giants over New York Yankees (5-3)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ "1922 World Series – New York Giants over New York Yankees (4-0)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ Cohen, Robert W. (2012). The 50 Greatest Players in New York Yankees History. Scarecrow Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-0810883949. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ The Milwaukee Journal[permanent dead link] via Google News Archive Search

- ^ The Day via Google News Archive Search

- ^ "Home Run Baker father of twins" (PDF). The New York Times. February 3, 1914. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ^ ""Home Run" Baker's twins dead" (PDF). The New York Times. February 10, 1914. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ^ "Talbot Negro Held on Assault Charge – Seize by "Home-Run Baker" After Alleged Attack On Ball Player's Sister-in-Law – Big Posse Joins in Hunt – Suggestion That Suspect Be Lynched Silenced By Manager of Easton Club". The Sun. Baltimore. August 28, 1924. p. 1. Retrieved December 21, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Cep, Casey (September 12, 2020). "My Local Confederate Monument". New Yorker. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "Home Run Baker Recovering". The New York Times. The Associated Press. June 23, 1963. p. 4S. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ "Home Run Baker Dies at 77; Slugger in Era of the Dead Ball – 3d Baseman in the Athletics' $100,000 Infield – Later Sold to the Yankees An Auspicious Start Sold to Yankees". The New York Times. The Associated Press. June 29, 1963. p. 23. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ a b James, Bill (2001). The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. Simon & Schuster. pp. 548–550. ISBN 0-684-80697-5.

- ^ The Day via Google News Archive Search

Further reading

[edit]- Sparks, Barry (2005). Frank "Home Run" Baker: Hall of Famer and World Series Hero. McFarland. ISBN 0786423811.

- Jones, David. "Home Run Baker". SABR. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- Obituary via The Deadball Era

External links

[edit]- Home Run Baker at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from Baseball Reference, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Home Run Baker at Find a Grave

- 1886 births

- 1963 deaths

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- Major League Baseball third basemen

- Philadelphia Athletics players

- New York Yankees players

- American people of English descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- Baseball players from Maryland

- American League home run champions

- American League RBI champions

- Minor league baseball managers

- Baltimore Orioles (International League) players

- Reading Pretzels players

- Easton Farmers players

- People from Talbot County, Maryland